Jeni and Ray Bonell planned for four kids—but ended up with 16, becoming Australia’s largest family. Living in Toowoomba, their home is filled with kids aged 10 to 35, plus grandkids, making life busy, loud, and full of love.

Jeni spends around $600 weekly on groceries, buying 50 liters of milk, dozens of eggs, and more to feed the crowd. Daily life is a mix of school runs, sports, chores, and dinners for 20. She shares budget meal tips online, sometimes feeding the whole family for just $2 per person.

Kids start helping from age eight, and by 12, some cook full roast dinners. With six loads of laundry a day and no government support, the family runs on planning, teamwork, and faith.

Through it all, Jeni and Ray stay strong as a couple.

Their story shows how love, humor, and routine can keep even the biggest families running smoothly.

Meet The Bonell Family: What It’s Really Like Being The Father of 16 Kids

There’s an old joke from comedian Jim Gaffigan. “You know what it’s like having a fourth kid? Imagine you’re drowning, then someone hands you a baby.” If you accept that logic, Ray Bonell must be at the bottom of the deep blue sea.

Ray is possibly the world’s most persuasive man. When he first met his wife Jeni, she didn’t want to have any kids. Now they have 16.

The Toowoomba family consists of nine boys and seven girls with ages ranging from 29 to four. The brood includes: Jesse, Brooke, Claire, Natalie, Karl, Samuel, Cameron, Sabrina, Tim, Brandon, Eve, Nate, Rachel, Eric, Damian and Katelyn. Just don’t expect Ray to be able to reel off all the birthdays…

Here, the 51-year-old electrician, reflects on what life is like as the father of Australia’s largest household.

After we’d had a couple kids, I actually thought: ‘Well, two’s probably enough.’ But you only know what you know. Jen wanted to have a third one and then three just sort of blossomed… into 16.

Yes, I do have a TV.

What’s the best thing about having such a big family? All the hugs and kisses. Even to some extent, all the challenges. Trying to just manage this many personalities in the one family. It never gets boring. You never know what you’re going to be faced with on a day-to-day basis.

We’re always very conscious that we’re raising 16 individuals. We’re not just a factory line producing kids who are all the same. And, as a parent, it’d be disappointing if they were all the same.

Having this many kids – you obviously don’t get there by accident. It’s the life choice that’s right for my wife and myself. We don’t expect anyone else to go out and have 16 children. People have to do, what’s right for them. And look, it is stressful, right – having this many children is not for everyone. But it just feels right for us.

I go out to work each day as an electrician. The ‘transporter’ in our household is my wife – her daily run-around vehicle is a 16-seater bus.

The biggest challenge in having such a large family is probably feeding them. We go through one or two loaves of bread a day and up to six litres of milk. We have to go to the grocery store a few times a week because if the kids come home after a hectic day at school and feel really hungry they can empty the whole pantry.

Years ago when we just had our first five children I remember looking at the oldest one who was about seven years of age. Back then, I used to work long hours. And I just had this realisation where I thought: I’ve missed these five kids growing up. That’s when I made a conscious decision to prioritise raising my children over work.

I’ve been really, really lucky that we’ve had more children and I’ve had that opportunity to watch the rest of them grow and not put work first. I’m also lucky to have a fairly good job that does pay the bills. But I work to live, I don’t live to work. Spending time with your children is very fleeting.

We have a roster system in our house, so when one of the kids turns eight, they get put on the roster. There’s a list of about six or seven chores that rotate them during the week. Sweeping, washing the dishes, mopping the floor, packing up the table, helping us to prepare a meal.

Do I ever get to spend any alone time with with your wife? Well, obviously I do, yeah. Otherwise we wouldn’t have 16 children. But my wife and I will sometime go out and have breakfast together. Or if one of the older child is here and we’ve got a spare half an hour, we’ll grab a coffee together on our own. We have to make that a priority. We’ve got to look after each other. It’s true what they say: happy wife, happy life.

What is the secret to a successful happy marriage after having kids? Patience and tolerance. Luckily, my wife is very patient and tolerant with me.

We don’t tend to go on family holidays. But this year we decided to get most of the kids together. My wife took care of a lot of the stress and the planning. She used booking.com to help organize it all. We went to Port Douglas and it was just incredible. There was 21 of us in total – 15 of the 16 kids and then some of their partners and also one of our grandchildren. For many of the family it was the first time they’d ever been on a plane. It was an awesome trip.

Getting a good family photo is difficult. You need an extra wide lens on your camera and there’s always someone who’s looking away or has their eyes closed or pulling a funny face. But we enjoy those little quirks in the photos. They’re not picture perfect, but that’s just part of the fun

We have 16 kids and just one bathroom. One bathroom to feed all these kids through.

All pictures from Instagram: @thebonellfamily_

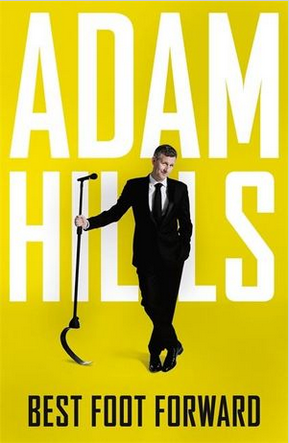

Adam Hills: “Fatherhood Changed The Way I Work. It Made Me More Focused”

Comedian Adam Hills reflects on his relationship with his dad, his inherited love for the Rabbitohs and his advice for any new dad.

Bob Hills, my dad, worked in the Qantas cabin crew. The inflight motto, he always used to say, was: “If it moves, call it sir. If it doesn’t put parsley on it.

As far as I was concerned, my dad’s job was to fly around the world and talk to people over the microphone. Is it it any wonder that I do what I do now?

How did my dad influence me? Well, on holiday, when I was about eight, I remember someone calling him “the nicest man in Qantas”. That made me proud. You want to be like your heroes and my dad was definitely one of my heroes.

When I was three-days-old, my father brought a red and green toy rabbit into the hospital to ensure that I’d be a Rabbitohs fan for life. He always took me to the game as a kid – we talked about them all the time. When dad died, his Rabbitohs hat was on the bed next to him. That toy rabbit now sits in my daughters’ playroom.

It doesn’t matter how long ago it is that you lose someone. You have those moments when you want to tell them something. When the Rabbitohs played the 2014 Grand Final, I flew back from London to watch them win. After the game we were all singing: “Glory, glory to South Sydney”. Suddenly, I had tears in my eye because I just wanted to turn to my dad and put my arm around him. It’s a ridiculous thing the way sons bond with their fathers over sport.”

Having kids did change me (Adam has two daughters aged 6 and 10). I think fatherhood makes you more confident in yourself. More grounded.

As a father you need to be present. When my dad was away for work he’d be away for days and weeks at a time. But when he was back he always had all the time for you – we’d come back from school and sit together and watch cartoons. When I’m with my kids I always try not to do anything else.

Fatherhood changed the way I work. It made me more focused. It made me not want to take every single gig. I’ll only do them now if I think they’re worth it. I’ll turn down corporate jobs, say, because I want to be back home for bedtime.

What advice would I give to a new dad? Don’t get too down on yourself when you do something wrong. If you lose something, put a shoe on the wrong foot, lose your temper… just go easy on yourself. As long as you’re trying to be a good dad that puts you way ahead of the game.

I was holding my dad’s hand when he took his last breath. It was both beautiful and terrible. In some ways it was the worst moment of my life. But to be able to be there for him meant a lot.

Adam Hills autobiography Best Foot Forward is out now. Buy it here

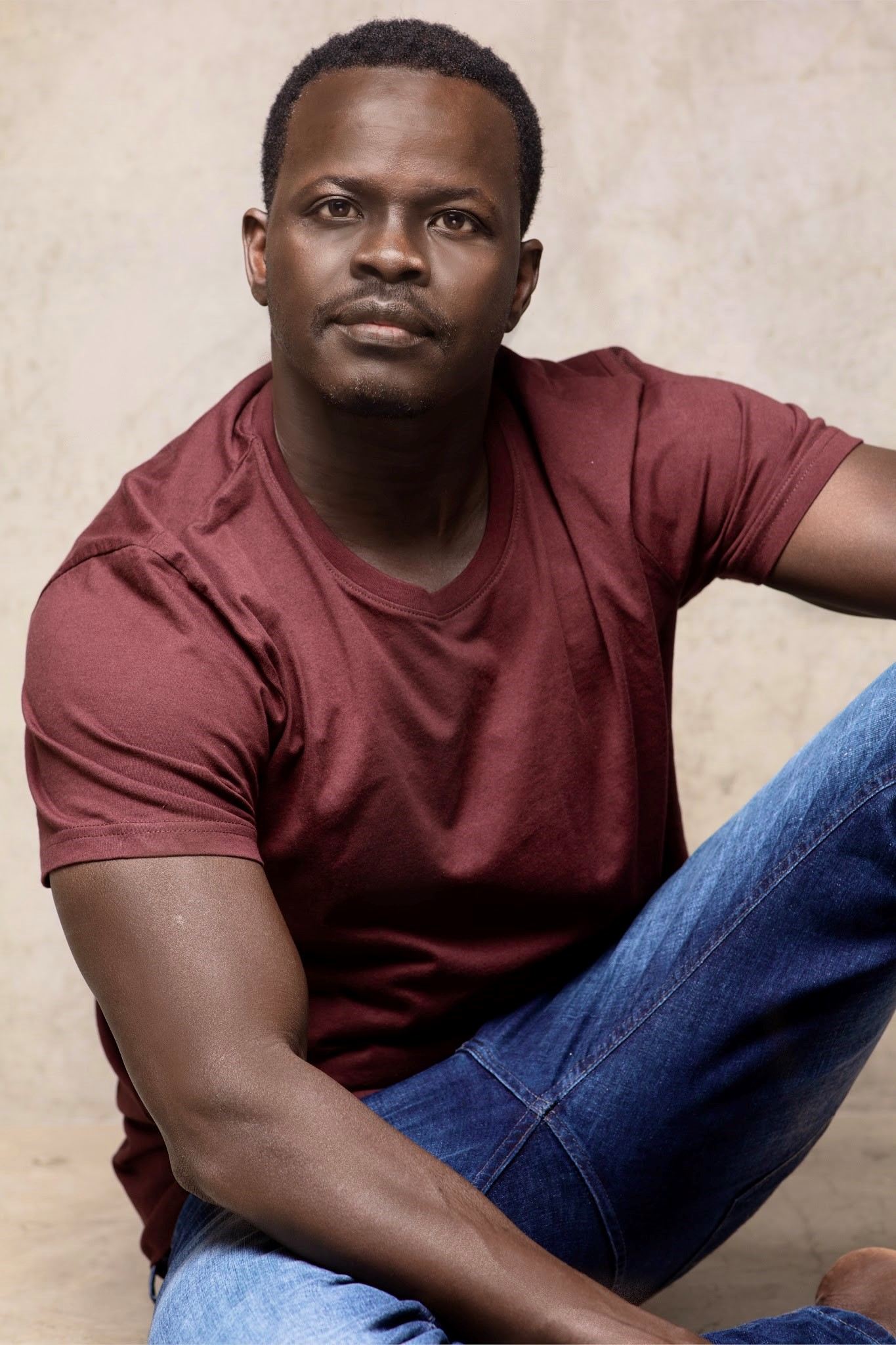

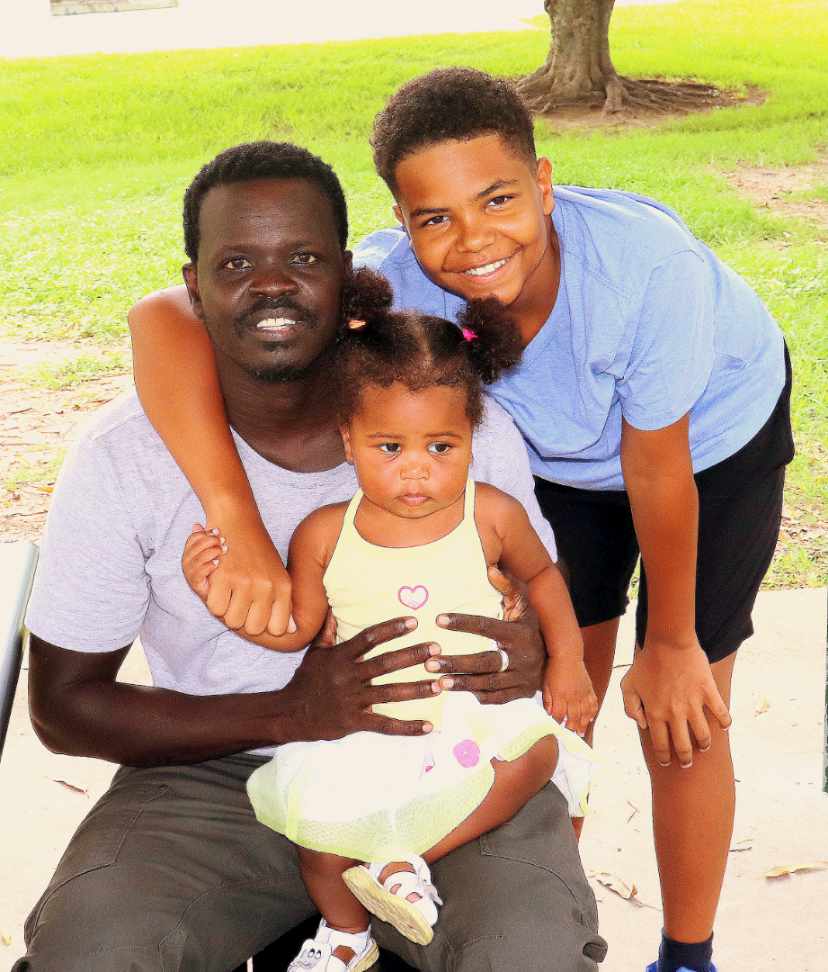

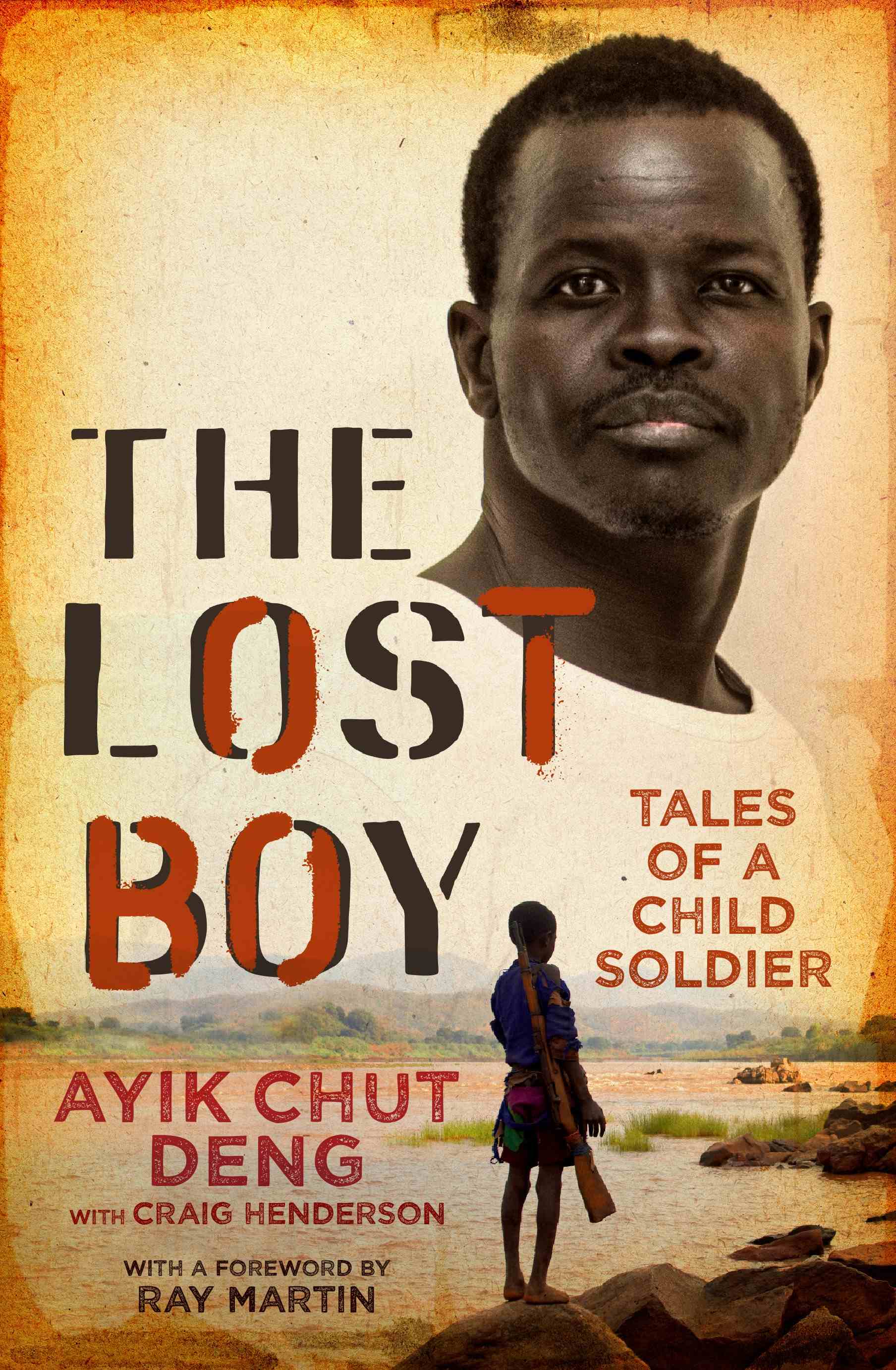

Ayik Was 13 When He First Used An AK-47 – That’s The Same Age That His Son Is Now

It’s been a wild ride for Ayik Chut Deng. He survived unspeakable violence as a child soldier in the Sudan, before moving to Queensland as a refugee in 1996.

But for a while, life was turbulent here, too. After his post-traumatic stress was misdiagnosed as schizophrenia, Ayik was wrongly medicated. He began abusing drugs and alcohol, clocking up a slew of criminal charges ranging from drug dealing to drink driving. “It was being a father that sorted me,” he says. “That gave me something to live for.”

Here, Ayik explains how he turned his life around and why – after everything he’s lived through – he can handle the craziness of being a single dad.

Australia is one of the best countries in the world. If I’d gone to America, I’d be dead by now. I’d have joined a gang – of course, I’d have joined! I was into guns due to my past as a child soldier.

When my child was born in 2006, I was at the birth in the hospital. But the love wasn’t as strong as it is now. I reckon the love of a father builds and builds over time.

At the time when my son was born I was on medication. I’d been misdiagnosed with schizophrenia instead of post-traumatic stress disorder. But at the same time I was using illegal drugs – weed and ecstasy – but I was also drinking.

His mother left me in 2008. I was mixed up in the drug world and lost track of where I was going in life. She said, “You’re going to get locked up, so there’s no point – I’m leaving.”

That did wake me up. After that I realised, OK, I’ve been on medication now for six years and I’m not getting better, I use illegal drugs and my partner left me because I wasn’t doing anything with my life. That’s when I stopped using drugs.

The problem was that I started drinking more instead. There was a time when I used to wake up and grab a beer out of fridge. It was like a breakfast.

I stopped drinking in 2013. It was being a father that sorted me. What happened, I realised that I was raised without a father – he was killed at the start of the war. And I realised that although my son had a father, I had a problem. So I decided to stop drinking to be able to connect with my child.

I wanted my kid to know what it’s like to have a father, because I missed out on all that. And being a child soldier too, I wasn’t raised with my own family so I missed out on my own childhood, too. When I play with my son now, I’m living my childhood through him.

I feel good when I’m with my son. I feel really good that somebody is looking up to me, and I’m making promises that I stick to. I don’t break my promises with my children.

It took me a long time to get access to him. But my message to dads who don’t have access to their kids is never, ever, ever give up. Now I have joint access. At the moment I’m getting along pretty good with the mother and I try and help her in every way.

But now I’m also a single dad raising a child by myself. My daughter is 16 months old – she was given to me when she was only eight days old. Her mother had drug problems, which I never knew when I first met her. It was a one-night stand and she got pregnant. So when Sunday was born, the child safety called me and said: “This is your child – the mother can’t keep her. Are you going to take the baby or not?” It took me half an hour to make my mind up.

Being a single dad – okay, it is hard, especially the first few months when the baby wakes up every single hour. But it’s not as hard as how some people describe it. All the baby wants is to be fed, loved and cared for. You keep them clean, you give them lots of attention and then I think you are covered, honestly. All you can do is you take it day by day.

And I’ve been through worse my life. I suffered in the war as a child soldier. I’ve been shot at. I’ve been bombed by jet fighters. I’ve been ambushed. In Africa, there were times when I had to eat rats and drink my own urine. Compared to that being a single dad isn’t so hard.

What advice do I give my son? I tell him: “Always give everybody a chance. Don’t judge people before you get to know them. Your friend’s enemy might be the best friend to you in the long term.”

I tell him: “I lost my dad when I was very young and my grandmother was burned to death. Just remember: we’re not going to live forever. So the time you have, live it well and be nice to people!”

I tell him: “If I die, you take care of your little sister. Take care of Sunday.”

I’m getting some work now as an actor. I signed a contract today for an ABC series. I really want to work on Thor: Love & Thunder with Chris Hemsworth. My favourite movie of all time is Commando with Arnold Schwarzenegger – that was the first movie that I ever saw.

My best achievement, the only thing that I’ve ever really achieved in this life, is my two children. There’s nothing else. My acting, all these things don’t count to me. My children make me happy, and I hope one day they will make other people in this world happy, too.

The Lost Boy by Ayik Chut Deng is out on March 31. Pre-order it here

Vincent Fantauzzo: “I Really Wanted To Become A Dad But I Was Also Scared”

Vincent Fantauzzo’s life has a storybook trajectory. Today the 42-year-old is one of Australia’s most famous artists, an Archibald Prize winner who’s married to the beautiful actor Asher Keddie. But his future didn’t always look so promising.

Vincent grew up dirt-poor in Melbourne’s Broadmeadows, sharing a two-bedroom commission house with his mother and four siblings. He left school at 13 barely able to read or write – his severe dyslexia was only diagnosed in his 20s. Consequently, Vincent got mixed up in street-fights and general delinquency; he’s even admitted to carrying a gun for a while in his teens.

Luckily, his formidable talent with a paintbrush enabled him to break free and build his successful career. But that troubled background also meant he was initially daunted by the prospect of fatherhood – Vincent has two boys Luca (10) and Valentino (4). Here he talks about fostering creativity in your children, the value of building confidence and why you don’t have to be a dad to be a father figure

“I always thought that I would be a father at some point. I really wanted to become a dad, but I was also scared, I think because I had my own difficulties growing up and there was also a bit of a panic: what if I can’t live up to the expectations that I had for myself? If I have a boy, I thought, there’s a lot of pressure there – I don’t want to set the wrong example or let them down.”

“I knew that I wanted my kids to grow up one day and say that they had a great dad. I didn’t have a lot of great male role models growing up, so I didn’t want them to have the same experience.”

“But I remember I called up Matt Moran – who’s a good mate of mine – and he was the first person I told that I was going to become a dad. Matt just said: ‘It’s going to completely turn your life upside down forever and it’s going to be the best thing that’ll ever happen to you.” And it was. Nothing has ever been the same.”

“My dad, Claudio, wasn’t a bad person. It’s just I didn’t get to develop that relationship because it just wasn’t available to me (Vincent’s parents split up when he was in Grade 6). And I think it affects everyone differently.”

“Some people aren’t fortunate enough to be able to have children biologically. But that doesn’t mean they can’t still play a really strong fatherhood role in someone’s life. Yes, being a dad changed my life. But there are people that are uncles who’ve also been changed by the experience. A boxing coach, an uncle, a friend, a cousin – they can all be fatherly figures. It’s important to acknowledge that. They can still play that fatherly role to someone in another way. Similarly, if a kid isn’t fortunate to have a biological father, he can still experience the joys of having a positive male role model in their lives.

“What advice would I give to a dad whose kid was dyslexic? From a parental perspective, it doesn’t really matter what the specific issue is – your kid might be dyslexic or have a learning disability or a weight problem. I think it’s about finding the things that make them confident and not expecting them to be able to do the ones that will never be possible for them – like maths was for me! Focus on something that your kid is good at instead. It’s about having the patience and recognising that everyone’s an individual. It’s like I loved boxing as a kid and I tried to introduce martial arts to my boys and they’re just not interested. They like playing soccer. So now I’m trying to learn how to play soccer badly. Maybe one day they’ll ask me to teach them some boxing.

“What have I found the hardest part about being a dad? I find it a lot harder to concentrate on my work because I don’t want to miss out or let them down. Sometimes I feel like I’m letting myself down work-wise because I’m putting a lot of effort into being a dad. And then it’s about trying not to be frustrated or resentful about how I’ve spent that time.

“It’s the eternal problem. You hope that being successful at work is also going to inspire your kids and make them look up to you. But not being there for a soccer game would make them feel let down. That’s a tension that I’m constantly aware of.

“There is so much Lego around our home. Just the other day, Luca and I came up with this superhero character – Val was helping us as well – and we decided to build the character’s lair using all these different bits. We ended up building for four or five hours straight. My back was killing me, I was all hunched over, getting all serious trying to find these pieces. It was just an afternoon spent building Lego. But hopefully it’ll be the sort of moment that my kids remember.

“I think the key to encouraging creativity in your kids is to keep it fun. It shouldn’t feel like homework. And ideally, if you can find something that you can enjoy doing with them yourself then do it together. But making it fun is key: if your kid’s drawing a picture, don’t tell them that the eyes are in the wrong place. Just let them draw.”

How To Cope With A Massive Curveball – What I Learnt From My Brain Tumour

Paul Edwards recently was delivered the news that no one ever wants to hear – you’ve got a brain tumour, it’s very large, and it’s going to take big-time surgery to get it out.

Speaking from his recovery bed only one month after surgery, Paul shares the surprising positives that he believes could help any dad facing a life-changing curveball. “Laughter is the greatest healing medicine there is,” he explains. “Behind Endone, of course.”

1. Acknowledge the big fear and don’t bullshit the kids

“The greatest fear when illness happens is always – will that person die? I have twin 14-year-old girls and their only exposure to death has been an old dog and a friend’s daughter who died aged seven from a cancerous brain tumour. This was the sum total of their limited experience of death.

“Understandably, my diagnosis brought a lot of fear and uncertainty into the house. I decided it was OK at my girls’ age for them to see me process this possibility openly, not in private. We talked about death – it was unlikely, but it was discussed.

“We also decided early to not bullshit to the kids. Whilst we were delicate with the terminology we used, kids’ bullshit meters are set bloody low these days. They can Google ‘brain tumours’ and calculate your survival predictions to the nearest percentage. And they did. It was important for the trust bond not to be broken. Listen, acknowledge and respond to their fears openly.”

2. Family is everything – work as a team

“When I got the phone call you never think you’ll get it was a huge shock. But the good part was the family unit swung into action immediately. It was like a friggin’ SWAT team. We did stuff we’d never done before. We had to be real.

“First up, we had a family meeting and established a team mentality that was: “We’re in this together”. A bond was created immediately and petty rivalries were put in perspective.

“This is the single most comforting thing you can experience as a sick father. Pure unconditional family love through a common goal – albeit coping with my possible but unlikely death.

“The family unit is based on roles and responsibilities. Typically the parents fulfil both – mum does this, dad does this and all I need to do as the child is clean my room, do my homework and not be a dickhead. Putting individual and team responsibilities onto two 14-year-old girls is a major mindset shift.

“The truth is it took weeks for both kids to step up. Not to say they didn’t care, but they don’t know what they don’t know. It took a while for everything to sink in – they were functioning in a state of uncertainty.

“Once we realised this as parents, we both looked to create certainty, reset our roles and deal only in the known. We set timelines, boundaries, open communication and, all of a sudden, the family started to resemble a high-performing team. Everything became easier.

“That was the coolest feeling ever as a dad, to see your children accepting responsibility and taking action. Our team affirmation was “We’ve totally got this”. We kept repeating this and one of my daughters even wrote it on a heart and put it in my toiletry bag which I found just before I went if for my Craniotomy.”

3. Discover the power of gratitude

“OK, so here’s the big message and learning. We started to look for the gifts in the whole experience and feel gratitude everywhere for little things we never noticed before.

“It was about finding the upside to every micro experience. For the girls – on a small scale – hospital visits meant treats, their mum could now drop them at school not the bus stop and they started having more meaningful conversations with their friends. But there were abundant green shoots of positivity in everything. Every experience was looked at through positive minds.

“We invented ‘tumour humour’. Laughter is the greatest healing medicine there is, after Endone, of course. Love came into the family everywhere. And with love came gratitude for each person. Suddenly, this whole thing started to look like a win. Who saw that coming? Not me.

“When the family started functioning as unit we realised the game had changed. The truth is this has been the best experience for the family. One we’re now actually grateful for. Buddha says learn to love what you hate and hate what you love. We’re now grateful for the illness.

“For me, I was particularly grateful for the smaller authentic moments. I so appreciate all the girls’ support and seeing who they really are. They have, in turn, witnessed me overcoming pain, uncertainty and returning to be a stronger man who’s more vulnerable both emotionally and physically.”

4. Love their Mum openly

“As a father the coolest thing you can give your children I believe, is to love their mother. This sets up so many of their values.

“During this experience, my daughters have seen us come together the way we did when we were in our 20s, and they just dine out on it. You can see and feel the joy they get from seeing their parents unite – just like Dale In The Castle!! That’s a hugely powerful gift in itself.

“So there you go. What could have been an incredibly bleak and destabilising experience has, in the end, well and truly opened our hearts. As a father, my brain tumour has been a profoundly positive experience and one that I’ll use to become a better leader in other areas of my life.”